DRAMATURGY:

OUR PLAYS IN CONTEXT

Two Big Black Bags

|

|

|

For the best reading experience, click here to access a pdf of the following dramaturgical notes and learn more about the play's context.

Two Big Black Bags Full Play Program

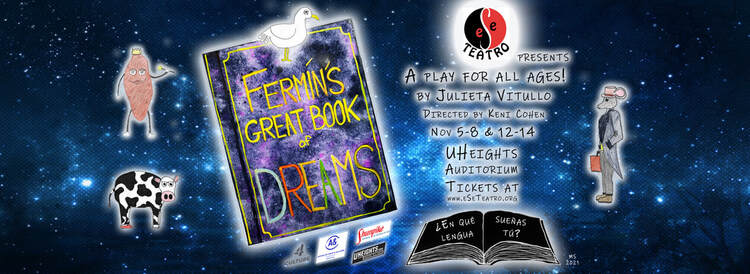

Fermín's Great Book of Dreams

Notes and Dramaturgy by the Playwright

When I first thought of an encounter between Ratón Pérez and the Tooth Fairy, I believed I had had the most brilliant and original idea. After writing a couple of scenes, I found out through the internet that someone had already thought of that encounter. A picture book exists about a meeting between the Mouse and the Tooth Fairy, and apparently someone wrote a musical based on it. I felt despondent until I realized this idea was just the seed for something much bigger that had yet to be written. I started thinking about other stories from my childhood, impressions that have lived inside me for as long as I can remember. As those impressions began to shape up, they became fresh versions of characters from songs I grew up listening to, songs by Argentine singer and songwriter María Elena Walsh that introduced me to a world of whimsical poetry and imaginative characters at a very early age.

María Elena Walsh (1930–2011) was a poet, novelist, musician, playwright and composer mainly known for the songs she wrote for children starting in the sixties. Many generations have grown up with songs such as “Manuelita la tortuga,” “Canción del jacarandá” and “Canción de tomar el té.” Her work features animal characters, plants, trees and inanimate objects in unusual and memorable situations. She may be one of the first widely known Latin American artists to have incorporated the concept of cultural identity into children’s songs. Her language is musical and accessible, full of imagery and metaphors, and her melodies, sophisticated yet simple, present a mix of classical and Latin American folklore rhythms.

Fewer authors have stimulated the early inner workings of my imagination than Walsh, so the arrival of those characters in my creative process felt natural. But these creatures didn’t appear to me quite as they appear in the songs--and neither does Ratón Pérez bear much resemblance to the character in the story by Spanish writer Luis Coloma that gave origin to the legend. They started to evolve in different directions, and I figured they each had given me so much when I was a kid that it felt only fair for me to give something to them by bringing them back life.

The idea for Abuela came up because I can’t think of my childhood without conjuring up my two grandmothers and the stories they told me before they both “crossed the bridge” when I was eleven. Like Walsh’s song “Marcha de Osías” says,

I want tales [...] but not tales that work by pressing a button.

I want tales held by the hand of a grandma

who reads them to me in her nightgown.

Imagination and stories are the most powerful weapon we have against adversities. As long as we can hold on to them, we’ll be invincible.

María Elena Walsh (1930–2011) was a poet, novelist, musician, playwright and composer mainly known for the songs she wrote for children starting in the sixties. Many generations have grown up with songs such as “Manuelita la tortuga,” “Canción del jacarandá” and “Canción de tomar el té.” Her work features animal characters, plants, trees and inanimate objects in unusual and memorable situations. She may be one of the first widely known Latin American artists to have incorporated the concept of cultural identity into children’s songs. Her language is musical and accessible, full of imagery and metaphors, and her melodies, sophisticated yet simple, present a mix of classical and Latin American folklore rhythms.

Fewer authors have stimulated the early inner workings of my imagination than Walsh, so the arrival of those characters in my creative process felt natural. But these creatures didn’t appear to me quite as they appear in the songs--and neither does Ratón Pérez bear much resemblance to the character in the story by Spanish writer Luis Coloma that gave origin to the legend. They started to evolve in different directions, and I figured they each had given me so much when I was a kid that it felt only fair for me to give something to them by bringing them back life.

The idea for Abuela came up because I can’t think of my childhood without conjuring up my two grandmothers and the stories they told me before they both “crossed the bridge” when I was eleven. Like Walsh’s song “Marcha de Osías” says,

I want tales [...] but not tales that work by pressing a button.

I want tales held by the hand of a grandma

who reads them to me in her nightgown.

Imagination and stories are the most powerful weapon we have against adversities. As long as we can hold on to them, we’ll be invincible.

Ratón Pérez

This character originates in an 1894 book by Spanish Jesuit priest and writer Luis Coloma (1851-1915). Regent queen Maria Christina of Austria commissioned Coloma to write the story for her son, future

king Alfonso XIII of Spain, when he lost a tooth at age eight. The story features King Buby (Alfonso's

nickname) and a good-heartedmouse who teaches him about the importance of being generous and brave. The boy turns into a mouse when Ratón Pérez sticks his tail into the boy's nose and makes him sneeze. The two of them go on an adventure to meet Ratón Pérez’s mice family and visit the house of a poor boy who has also lost a tooth. At the end of the night, Buby turns back into a boy and finds himself in his mother’s arms. The story is a vindication of monarchy and elaborates on the idea that kings are wealthy so that they can take care of their poor vassals (!). In the story, Ratón Pérez lives with his family inside a large box of cookies in a grocery store at confitería Prast, a well-known bakery and pastry shop in the heart of Madrid.

(Above, Ratón Pérez's statue in Confitería Prast)

king Alfonso XIII of Spain, when he lost a tooth at age eight. The story features King Buby (Alfonso's

nickname) and a good-heartedmouse who teaches him about the importance of being generous and brave. The boy turns into a mouse when Ratón Pérez sticks his tail into the boy's nose and makes him sneeze. The two of them go on an adventure to meet Ratón Pérez’s mice family and visit the house of a poor boy who has also lost a tooth. At the end of the night, Buby turns back into a boy and finds himself in his mother’s arms. The story is a vindication of monarchy and elaborates on the idea that kings are wealthy so that they can take care of their poor vassals (!). In the story, Ratón Pérez lives with his family inside a large box of cookies in a grocery store at confitería Prast, a well-known bakery and pastry shop in the heart of Madrid.

(Above, Ratón Pérez's statue in Confitería Prast)

Most cultures across the world have a ritual around losing teeth--from leaving the tooth under the pillow for a mouse or a fairy to pick up, to throwing it over the roof, to burying it, and more.

Gaviota Marmota

María Elena Walsh’s song “El show del perro salchicha” features una gaviota medio marmota-- literally, a seagull that’s a bit of a marmot--and picks up a Dachshund from the beach after mistaking it for a shrimp.

|

Perro Salchicha, gordo bachicha,

toma solcito a la orilla del mar. Tiene sombrero de marinero y en vez de traje se puso collar. Una gaviota medio marmota, bizca y con cara de preocupación viene planeando, mira buscando el desayuno para su pichón. Pronto aterriza porque divisa un bicho gordo como un salchichón. Dice “qué rico” y abriendo el pico pesca al perrito como un camarón. Perro salchicha con calma chicha en helicóptero cree volar. La pajarraca, cómo lo hamaca entre las nubes y arriba del mar. Así lo lleva hasta la cueva donde el pichón se cansó de esperar. Pone en el plato liebre por gato, cosa que a todos nos puede pasar. El pichón pía con energía, dice: “Mamá, te ha fallado el radar; el desayuno es muy perruno, cuando lo pico se pone a ladrar”. Doña Gaviota va y se alborota, Perro Salchicha un mordisco le da. En la pelea, qué cosa fea, vuelan las plumas de aquí para allá. Doña Gaviota: ojo en compota. Perro salchicha con más de un chichón. Así termina la tremolina, espero que servirá de lección: El que se vaya para la playa que desconfíe de un viaje en avión, y sobre todo haga de modo que no lo tomen por un camarón. |

A pudgy dachshund, fat, chubby, sausage

Is taking a sunbath way down by the sea. He’s got a cap on, just like a sailor Except for his collar, no swimsuit has he. A passing seagull, sort of a numskull, Cross eyed and showing a frown on her face Dives quickly, lurching, seems to be searching For tasty morsels to take to her nest. Quickly she’s landing and looks demanding, Shaking her feathers at what she has seen: She says “how tasty” and making hasty, Carries the puppy away like a shrimp The little puppy, fearless and happy, A helicopter hoping to fly. With the gull soaring, great heights exploring, Among the clouds and high up in the sky. Home they’re arriving, to the nest diving The baby seagull demanding his meal. His mother in rapture feeds him her capture, Never once doubting the shrimp was for real. Birdie’s complaining, loudly proclaiming: “Mother, you’ve once again made a mistake; My breakfast’s barking, my beak he is biting, This is no shrimp that you’ve brought to your babe”. So going thither, all in a dither, She looks at the dachshund and gives him a poke: Her beak is bitten, her feathers smitten. The fight is on and this time it’s no joke, A sore eye for Mistress Seagull. And the doggy black and blue. Thus the conclusion of the confusion, So this is my advice to you: When you are lying on the beach, tanning, Free trips on a ’copter you always must scorn, And, more important, take every precaution Not to let anyone think you’re a prawn. |

* Translation by: Poemas del Río Wang blog.

María Elena Walsh’s original songs, recorded many decades ago, can be found on her YouTube channel. They’re not to be mistaken with the versions found in a cover album with accompanying animated videos released in 2000.

María Elena Walsh’s original songs, recorded many decades ago, can be found on her YouTube channel. They’re not to be mistaken with the versions found in a cover album with accompanying animated videos released in 2000.

La Vaca de Humahuaca

María Elena Walsh’s song “La vaca estudiosa” features a cow who decides to attend

school along with the children in the town of Humahuaca, in the Northwest of

Argentina.

|

Había una vez una vaca

en la Quebrada de Humahuaca Como era muy vieja, muy vieja estaba sorda de una oreja Y a pesar de que ya era abuela un día quiso ir a la escuela Se puso unos zapatos rojos guantes de tul y un par de anteojos La vio la maestra asustada y dijo: “Estás equivocada” Y la vaca le respondió: “¿Por qué no puedo estudiar yo?” La vaca vestida de blanco se acomodó en el primer banco Los chicos tirábamos tiza y nos moríamos de risa La gente se fue muy curiosa a ver a la vaca estudiosa La gente llegaba en camiones en bicicletas y en aviones Y como el bochinche aumentaba en la escuela nadie estudiaba La vaca de pie en un rincón rumiaba sola la lección Un día toditos los chicos nos convertimos en borricos Y en ese lugar de Humahuaca la única sabia fue la vaca Y en ese lugar de Humahuaca la única sabia fue la vaca |

Once upon a time there was a cow

in the Humahuaca ravine As she was very old, very old she was deaf in one ear And even though she was already a grandmother one day she decided to go to school She put on a pair of red shoes tulle gloves and a pair of glasses Scared, the teacher saw her and said "you're wrong" And the cow replied: “Why can't I study?” The cow dressed in white settled down on the first desk We children threw chalk and were cracking up People arrived, very curious to see the studious cow People came in trucks on bicycles and on airplanes And as the ruckus increased nobody studied at school The cow standing in a corner ruminated the lesson all alone One day all the children turned into dumb donkeys And in that place of Humahuaca the only wise one was the cow And in that place of Humahuaca the only wise one was the cow. |

La Reina Batata

María Elena Walsh’s song “La Reina Batata” features a sweet potato queen whose

misadventures with the chef appear in the play as a background story.

|

Estaba la Reina Batata

sentada en un plato de plata. El cocinero la miró y la Reina se abatató. La Reina temblaba de miedo, el cocinero con el dedo -que no, que sí, que sí, que no- de mal humor la amenazó. Pensaba la Reina Batata: “Ahora me pincha y me mata”. Y el cocinero murmuró: “Con esta sí me quedo yo”. La Reina vio por el rabillo que estaba afilando el cuchillo. Y tanto, tanto se asustó que rodó al suelo y se escondió. Entonces llegó de la plaza la nena menor de la casa. Cuando buscaba su yoyó en un rincón la descubrió. La nena en un trono de lata la puso a la Reina Batata. Colita verde le brotó (a la Reina Batata, a la nena, no). Y esta canción se terminó. |

There was Sweet Potato Queen

sitting on a silver plate. The cook looked at her and the Queen got flustered. The Queen trembled with fear, the cook with the finger - a no, a yes, a yes, a no- in a bad mood he threatened her. The Sweet Potato Queen Thought: “Now he pokes at me and kills me.” And the Cook muttered: “I'll take this one.” The Queen saw through the corner of her eye that he was sharpening the knife. And she got so scared that she rolled to the ground and hid. Then came from the park the youngest girl in the house. When she was looking for her yo-yo she found the Queen in a corner. The girl put the Queen on a tin throne Little green tail sprouted (from Queen Batata, not from the little girl). And this song ended. |